by Barbara DiPietro, PhD, NHCHC Senior Director of Policy

Last month, I reflected on the death of Jordan Neely in New York City and how our society kills people three different ways: through direct physical violence (Murder #1), through indirect policy violence (Murder #2), and through silent ascent violence (Murder #3).

This month, I’m struck by the death of Tori Bowie, an Olympic athlete who died in childbirth in Orange County, Florida. Like Jordan Neely, Tori is Black, but unlike Jordan, she was not homeless—she had housing, resources, and strong support systems. Yet still she died. As it turns out, this isn’t uncommon in the United States, especially for Black women.

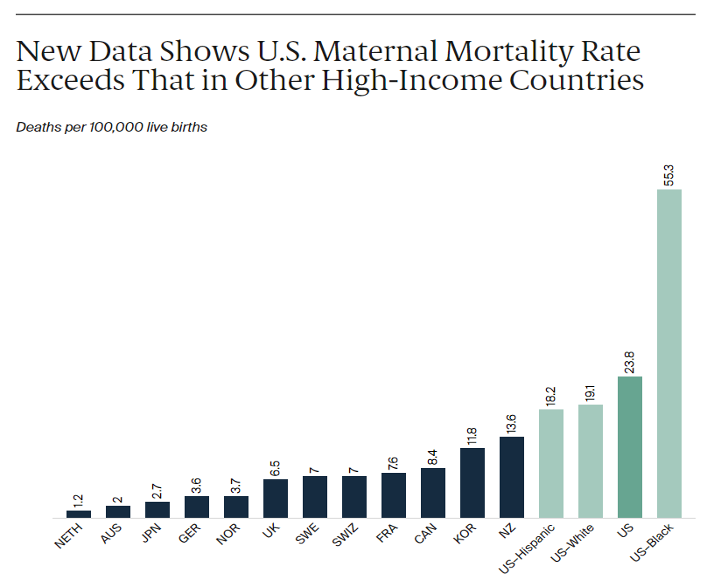

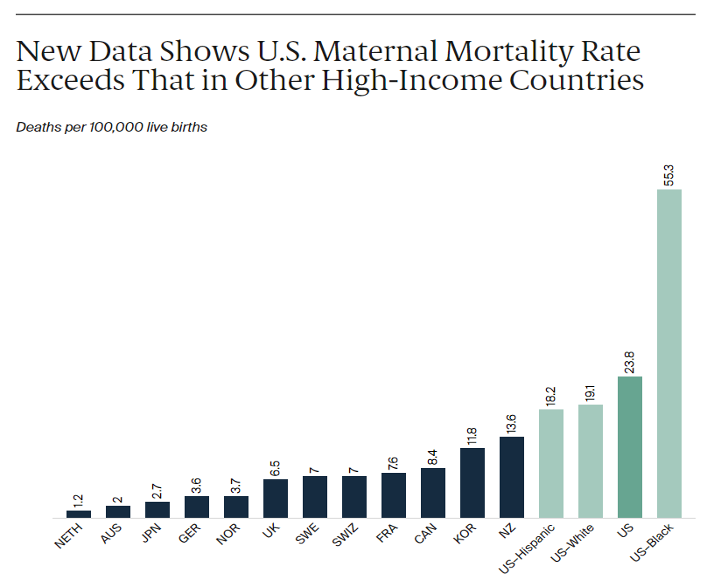

THE DATA: The maternal mortality rate* in the U.S. is nearly three times higher than in Canada—and the disparity with other developed nations is even greater (see figure below). However, disparities in maternal mortality within the U.S. show Black women dying at three times the rate of White women.

Source: The Commonwealth Fund, 2022

What’s causing our outrageously high maternal mortality rates—and what can we do about it? Let’s take a closer look at three aspects of indirect policy violence (Murder #2) that contribute to our extreme maternal mortality rates—especially among Black women: lack of access to health care, states with restrictive abortion laws, and lack of access to housing.

- Lack of Access to Health Care Coverage (Medicaid): Women of reproductive age who live in the 12 states where lawmakers have refused to expand Medicaid have significantly higher uninsured rates than women in expansion states—and two-thirds of these women in the coverage gap are people of color. Expanding Medicaid coverage has been demonstrated to lower maternal mortality, improve overall health, and support healthy development of both parents and children, especially among Black women. Simply put, health insurance saves lives.

- Restrictive abortion laws: It’s been one year since the repeal of Roe v. Wade, and evidence shows women living in states with abortion bans are three times more likely to die during pregnancy, in childbirth, or soon after giving birth. Other studies have found higher rates of maternal mortality and infant death (especially for women of color) and higher rates of death among women of reproductive age in general in states that have restricted abortion. States that restrict abortion are also states that have not historically supported women’s health in general.

- Lack of Access to Housing: It’s no surprise that homelessness is hazardous to a pregnancy. Women experiencing homelessness had significantly higher risks of pregnancy complications and go into pre-term labor more often than non-homeless women (even after adjusting for behavioral health disorders). Also, women facing eviction from their homes while they were pregnant are more likely to have poor birth outcomes. Housing provides the stability needed for a healthy pregnancy (and all other aspects of life).

“I was living in a vacant home in rural Alabama when I was pregnant, but getting care at the local clinic was not easy. I had to walk to get there, and I went twice to see a doctor and didn’t get help either time. Even though I qualified for insurance because I was pregnant, it took me weeks before I could get coverage and finally get seen by a doctor. The staff at the social services agency encouraged me to keep going back to the local clinic, but it should have been much easier to get the help I needed. I feel like being homeless and not being able to get health care endangered my health.”

~ Sandra Mooney, Consumer Engagement Coordinator, NHCHC

| * Important note: Transgender men and non-binary people who are pregnant face significant barriers to prenatal care (and other health care services) that cis-gender women do not. A 2019 LGBTQ Family Building Survey conducted by Family Equality found that 63% of queer and trans people age 18-35 were thinking about expanding their families, whether that meant becoming first-time parents or having more children. Our public policies need to reflect gender equity in pregnancy and childbirth. A prior Closer Look blog focused on the indirect policy violence that LGBTQ+ people often face. |

It cannot go unmentioned that direct physical violence (Murder #1) against pregnant women is shockingly high, largely stemming from intimate partner violence and firearms.

What’s Being Done to Address Maternal Mortality

In June 2022, the Biden Administration released the Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis, which included measures to improve access to coverage and care (to include HRSA funding for maternal health awards). More states are also expanding postpartum coverage for Medicaid—with 35 states and DC now offering a full year of coverage after delivery (though this no substitute for full Medicaid expansion). In April 2023, the Biden Administration lifted up the specific issue of Black maternal mortality by announcing the third annual Black Maternal Health Week to galvanize greater action to address the racial disparities in maternal health outcomes. Some states are also making strides to increase access to a broader array of services and providers that support maternal and infant health, diversify the health care workforce, and enhance data collection and reporting.

Indirect policy violence continues to murder pregnant women, with an outsize murder rate on Black women. But clearly more needs to be done if we are to drastically lower the U.S. maternal mortality rate and close the immense racial disparity gap among Black mothers.

Take Action

- If your state has not yet expanded Medicaid, advocate for full Medicaid expansion as quickly as possible. At the very least, advocate for 12-months of postpartum coverage.

- Call your federal representatives and ask them to co-sponsor the Medicare for All Act of 2023 bill that would bring the U.S. health care system in line with other developed nations.

- If your state has restricted access to abortion, advocate for access to comprehensive health care.

- Tell your federal representatives that the 25% budget reductions to HUD appropriations would only contribute to more homelessness and maternal mortality. Instead, much more should be invested in housing assistance.

“A Closer Look” is featured in the National HCH Council’s monthly policy action alert newsletter, Mobilizer. You can get Mobilizer sent to your email each month! Want to get a feel for it before subscribing? Check out the archives here.