More links related to these stories:

Kenneth “Ken” Goslin

– As told by Lindsey Krinks

Ken Goslin endured years of abuse as a foster child and experienced homelessness from age 14 until a brain tumor took his life in 2011.

Lindsey Krinks, homeless activist and co-founder of Open Table Nashville, tells his story.

A Cry for Help

The first person I was thinking about is a guy named Ken Goslin. Several years back I met him at the library park. I think why he approached me because he saw me working with other people. Sometimes the trust transfers. If other people trust you and see then they feel like they might can trust you, too.

It was so hot in July. We were both just drenched in sweat and he rolled up to me in his wheelchair and didn’t say anything to me, but he just scribbled this one word on a sheet of paper and held it up. That one word said “Help.” I said, “Well, what’s going on?” And he started writing.

It turns out he couldn’t talk or walk because of a brain tumor that was growing into his spinal column. And he hadn’t been getting the care he needed for that. He was staying, at that point, at the mission and would just wheel up and back. He couldn’t get any help because no one would spend the time just sitting down and trying to sort through everything.

In their own words:

Reaching out for help.

Running from Abuse

His mom was 17 when she had him. His dad was 21. They gave him up. He said he had never met his [family]… he just had his birth certificate. He knew the names, but he never was in a relationship with them. He grew up in foster care. He was born in San Francisco.

He traveled to Seattle, Georgia, Indiana, and other states… He was everywhere. He cycled through state custody and then foster home [after] foster home, where he said he was abused in every way possible—emotionally, physically, and sexually. At the age of 14, he was done.

There were stents of time when he was locked in a basement with a couple of other foster kids, and at 14 he said, “To hell with this,” and he left. So his homelessness started then.

He landed in Nashville after moving from Atlanta. I think part of it was running from his past and trying to belong, honestly. I think part of it was work. He was really adventurous. He could get around the city in a wheelchair.

He didn’t let anything stop him even when he couldn’t talk or walk. So I know part of it was for work, but I do think he was running from his past, too. Running from that abandonment and trying to belong in a deep, emotional way.

He was small, and strong, wiry arms with his wheelchair-calloused hands, and long hair that he pulled back under a ball cap. [He] was a really sweet guy. I think he was a chimney sweep for over a decade. I remember him saying he really liked going to people’s homes and making their pipes work again. He didn’t mind the dirty work. He did a lot of other odd jobs, too.

He would stay here or there. He never had a place where he had a lease and had stability. It would be with these friends, in this hotel room, doubling. He really wanted housing. The closest he found [to] community was in Atlanta with “Karen”—his adopted foster mom, who like us and took him in. She let him stay a couple of times, but he didn’t have housing there.

I think if he could have had housing that was dignified and not slammed into a project with thousands of other people, I think he would have absolutely loved it. That’s how I feel about so many of our people.

Entering Hospice Care

We started working together, and his biggest thing was that he received disability benefits, but those were coming through Chase Bank, and his bank card was cut off. So that was our first order of business. We figured that out. We got him his ID, and his birth certificate, but then a few months later he went into the hospital, and I could tell things were getting worse with his health.

He went into the hospital, and they told him, “You know, this tumor is going to kill you.” They said, “There are some operations we could do, but [for] the operations you have to have stable housing. There’s a lot of upkeep. We can’t guarantee anything.” After talking with the ethics people and with us, he just said, “I can’t do it, you know, I can’t go through that surgery, I don’t think it’s going to get better.” So we started moving to hospice care.

From there, we knew he didn’t have long. That was in December. He went into a long-term care facility where they lost his shoes, his wallet—everything he had. We had to rebuild all his documents.

Another facility that he moved into labeled all of his stuff… We finally were able to say this long-term care facility is not where he is going to find a dignified end of life. Because he had insurance and some money came through from one of his foster moms in Atlanta, we were able to get him into Alive Hospice, and he stayed at the Drake Hotel.

We became his family in his last months of life.

In their own words:

“The connection is the point.”

From a “Nobody” to a “Badass”

[His tumor] developed in his adulthood, and then it took away his ability to walk and talk, and then it took away his ability to swallow, so he had a feeding tube. He was shameless with his feeding tube. He’d say, “I still want to go to Starbucks,” and we were like, “Alright, Ken.” He would sit in the Starbucks, and he’s funneling his Starbucks coffee into his feeding tube. People are like, “What is happening?” But he was shameless, and I was, too. We were like, “Yes, this is happening.”

He would text us when we got him a phone, because that’s how he could communicate. He would end his text messages with a sign off, “I’m a nobody.” We’re like, “Ken, you matter. You’re a friend. We are here with you.” And we gradually got to see his “I’m a nobody” thing turn into “I’m a somebody.” And it eventually turned into, “I’m a badass,” which I love. He had a funny sense of humor. I really liked seeing his transformation from a “nobody” to a “somebody” to a “badass,” which shows you that he found his worth along the way as he was dying.

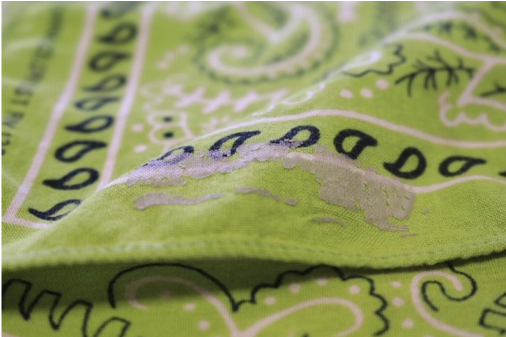

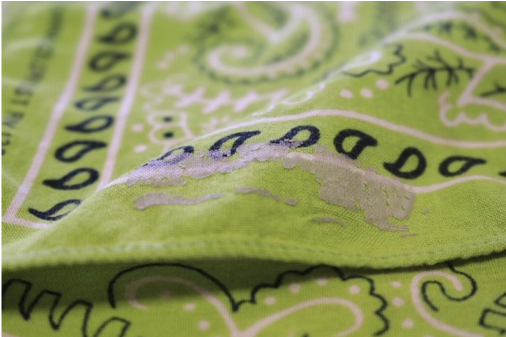

I brought some pictures and his bandana that I still wear. He was a very kind spirit. My favorite one [was] when he was Vanderbilt hospital. I like that picture of him a lot. That’s when we took him to see the Harry Potter film. He really liked tie-dye. Ken considered himself an old hippie, and he really loved tie-dye, so at the end when he actually moved into Alive Hospice’s facility, he was in gowns, and he wanted one of his gowns tie-dyed. So [our director] tie-dyed one. His hospice nurse did his last wish, taking him up in a hot air balloon. He was really supported and loved.

“That’s the Point”

He passed in August of 2011. I was there a few hours before he passed. I think he was waiting for me to leave, but we had people surrounding him around-the-clock when he was dying. One thing he could still do was smoke, so we took him a couple of days before his death. They have a smoking gazebo, and we would roll him out there. He could smoke a little bit, breathe in a little. That gave him some peace.

He wanted his funeral to be a celebration, so we all wore tie-dyed shirts, and we poured a cup of Starbucks coffee and a beer out in the ground where he was buried. We celebrated him and played “Free Bird,” which is what he wanted.

We buried him in a donated plot.

I remember when I went to get it the woman asked, “Is this your brother? Is this your uncle? Is this your father?” I kept saying, “No, no,” and she said, “Well, who is it then?” I said, “He’s my friend.” She said, “Is he homeless?” I said, “He was.” She said, “Why do you do this? Don’t you get attached?” I said, “That’s the point.”

That’s the point. This is community. It’s not a one-way street. The people we journey with are incredible.

Love, the Antidote to Bitterness

The Tennessean did a story on him. He was on the front page on Easter Sunday, and it said, “A Life Resurrected,” because he came into himself and his community as he was dying. It was the time that he felt the most alive and loved. He was one of the first people I journeyed with all the way in the dying process, so it made a big impact on me and us.

You know we’re building a micro village now for people that are struggling and don’t have housing, and I wish he could have been in one of our homes to find even more of that community, but we were able to journey with him. He taught us so much about resilience and love and humor and just survival and was stubborn in a really awesome way.

I always feel like the antidote to bitterness is love, and I think he did feel bitter for a long time, and then when he found the support and the care of a community that exterior started to soften a little bit. He isn’t a success story in one sense. We can’t say we got him into housing, and he’s still alive and he’s doing great, but we can say that there was an element of healing that happened at the end and that counts, too. It might not count on a grant, but it counts in our lives and in our work. Dying in a dignified way is really important.

More About Ken

- Bartoo, Carole. “On His Own Terms.” October 5, 2011. Vanderbilt University.

- Bob, Smietana. “A Life Resurrected.” The Tennessean, April 24, 2011.

Ken experienced multiple forms of abuse at an early age, and those traumatic events impacted the rest of his life. Like many others living on the streets, he was the victim of childhood trauma from abuse, neglect, and foster care—all of which are Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), the impetus for long-term adverse health outcomes and oftentimes homelessness.

Research shows that children without homes are more likely to have high ACE scores, increasing their risk of developmental challenges and poor health and functioning. The trauma of childhood abuse is also associated with behavioral health issues such as depression, aggressiveness, anxiety, memory problems, or posttraumatic stress disorder.

Homelessness itself is traumatic, and clinicians, homeless advocates, and health care providers should understand the impact of trauma when caring for and engaging with people without homes. Taking care to minimize re-traumatization by using trauma-informed approaches when serving people without homes is critical to positive health outcomes.

This means being aware of how trauma has impacted survivors and creating an environment of safety and trust. Providing trauma-informed care requires a shift in thinking from asking the question, “What’s wrong with you?” to “What has happened to you?” Implementing trauma-informed approaches is critical to improve the well-being and quality of life for people experiencing homelessness.

What can you do to stop homeless deaths?

Join us in working toward a world in which no

life is lived or lost in homelessness.