More links related to these stories:

Horace Horton

– As told by Lindsey Krinks

Horace Horton was 55 when he was killed during a violent altercation in his encampment.

Lindsey Krinks, homeless activist and co-founder of Open Table Nashville, tells his story. Krinks won the 2019 Porch Prize Winner in Creative Nonfiction for an article about Horace.

Meeting Horace

I worked closely with him several years ago. He was one of the guys that was always grumpy. If you were at a meal or a provider, he’d be the one hanging out in the corner, and you’d be like, “Oh gosh, I’m gonna avoid him.” He just had bad energy emanating from him.

I actually met him by accident. One of the guys I had housed was in an apartment and had Horace staying with him. The guy was refusing to go to the hospital, and so Horace looked up my number and called me and said, “I figured if anybody can get this guy to go, it’d be you, so will you get him to go?” And I said, “Well, let me try.”

And I did. I got him to go to the hospital, and Horace saved my number.

A few months later, Horace reached out. He was looking for a place to camp because he was on the streets and he needed housing and help. We met and we talked. We moved him into a campsite on the east side near Shelby Park, and he really loved having his own space and being with the birds and raccoons. He would put food out for them. The only thing that calmed him down was nature.

Lessening the Sting of Abuse

The more I started talking to him and watching how he interacted with everybody… he didn’t like people, people didn’t like him. He carried two pocket knives, one in his boot, one in his pocket, always ready for a fight. But the more I got to know him, the more I realized that he’s self-medicating with some deep stuff, and he has put these walls around him because things happened to him.

He would also mix drinks, so he would carry this big bottle of Hawaiian Punch and mix it with vodka. And it would look like he was drinking punch all day, but it’s spiked punch, “happy punch.” He would offer it to us all the time and we were like, “We know what’s in that punch, Horace; we’re not touching that.”

I started getting more of his backstory, and it turns out that he has been drinking since he was tiny. His uncles and aunts used to mix drinks like alcohol into his juice cups to calm him down when he was young. Later on, he had an abusive father, and he would start mixing his own drinks when he came home from elementary school to lessen the sting of his abuse and the anxiety. He had been using that as a coping mechanism since he was young and didn’t choose to start that.

He had had a bad divorce, and he lived in rural Tennessee before he came to Nashville. He lived in Knoxville before. He did a lot of construction work until his mental and physical health deteriorated and started self-medicating a lot more.

He has been to prison. He has hurt other people, and they have hurt him, and he had tattoos just everywhere. One tattoo was a Grim Reaper on his back. I was in the hospital with him several times, and his tattoos were a topic of conversation. He showed the nurses one time. They asked him something about death and he said, “I’m not scared of death.” He showed his Grim Reaper tattoo. The security guard was, of course, in the hospital with us because Horace was a handful, so he had security designated to his room.

The Wait for Housing

Horace wanted housing more than anything. I said, “Horace, if you’ll do your part, I’ll do mine, and you can’t be violent to me—you have to keep it cool. But I know you need and want housing, so let’s work together.” We started working on his housing and applying for Section 8, which takes a very long time, and finally, finally, finally, finally, after six months, his name got called for a voucher.

We had a hard time going to housing appointments because he also had a hernia, and since he didn’t have insurance, he had to wait for about two months to get his surgery because they wouldn’t operate. He had to go through the waiting list. So he was on the streets with a major hernia. But we finally got the housing paperwork through.

We had seen an apartment that was going to work out, and he loved it, but it was going to take another month, and in that time his tensions just escalated. Other people had moved into his camp by then, and he was convinced that people were stealing from him, they were convinced that he was stealing from them, and there was a lot of tension at his camp.

In their own words:

“The violence of the system.”

Opportunity Cut Short By Violence

He reached out to me for help, and I knew things were bad, so we tried to get him committed to Vanderbilt because he felt like hurting himself or others. But then he talked them out of committing him after I left, and they just released him, and he left [against medical advice].

A couple of days later a fight broke out in his camp with a younger guy, and they were both going at it. I wasn’t there, but I got a call the next night that something had happened and that I needed to come to his camp. I drove out to an area that was police-taped off, and there were flashing lights, and people on their walkie-talkies, and it was dark.

They had found Horace at his camp and needed help identifying him because of burns from a fight that he’d had [before having his body] put in a fire. He was killed at his camp by someone else I was working with about a month before he moved in, just weeks before he moved into permanent housing.

I don’t know if he would’ve been able to keep his housing, but he was willing to try and do what it took, and we were willing to support him through it. I feel like the best chance he had was cut short and taken away. We see the violence of the system that tells people “no” and tells people to wait and tells people, “We don’t have help for you unless you have the money and then the insurance.”

What’s sad is I also see on the streets is that people act out that violence and those tensions. They channel their frustrations toward each other. I think they were both doing that, and it just blew up. That was a really, really, sad thing. I got to meet his daughter through that. His daughter was at his funeral, and we took her to the campsite and put flowers there. But there’s a lot of loss that happened several winters ago. There’s a lot of trauma, a lot of violence.

He had been estranged [from his daughter]. He knew her early on, but I think what was interesting when I met her was she didn’t realize the struggles he faced. She just thought he was a bad dad, and once she heard a more about his backstory, she was like, “Oh.” It just helped her put some pieces together.

She found a little closure in that, in honoring him at his funeral. He talked about her. He wanted to reconnect. Once he got in housing he was trying, in his wounded ways, to figure it out.

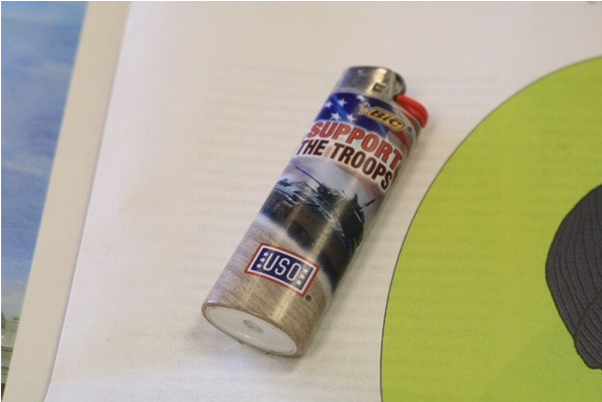

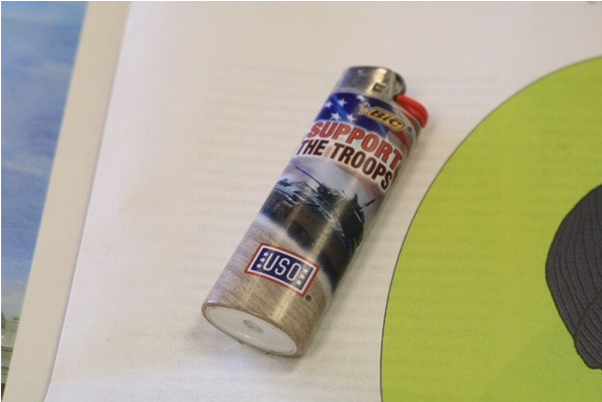

This is his lighter. It still works. I have a prayer candle I light from time to time at my house and I use his lighter.

“The Person that Everybody Would Dismiss”

The lack of affordable housing is one of the root causes of homelessness—we all know that. But interlocked with that is all these other systems, whether it’s people aging out of foster care and not having the support, disability rights, better benefits for people…I mean, can you make it on $774 a month? Not in this town. So, better resources, more accessible housing, and also more community support.

We always say if we just put a roof over everybody’s head, that would end homelessness. But it doesn’t do that internal healing work, and that’s where community and support and deeper sense of healing comes in, and we’re trying to do that at Open Table Nashville. I think the lack of support was huge in his life, too.

Like many people without homes, Horace turned to alcohol to cope with abuse and an unstable home as a child. Research shows that about half of adults experiencing homelessness have diagnosable substance use disorders. Furthermore, substance use and homelessness are bi-directional—the trauma of homelessness may create situations that lead to self-medicating, and addiction can create conditions that lead to homelessness.

Treating substance use disorder among people experiencing homelessness is made more complex since mental illness, trauma, and substance use disorder are often co-occurring. Successful treatment requires “providing comprehensive, well-integrated, client-centered services,” such as harm reduction strategies that focus on reducing adverse health and social consequences of substance use.

Additionally, the health benefits of permanent supportive housing are proven to play an important role in the successful treatment of addiction.

In their own words:

Horace’s tender heart.

One other thing I want to say about Horace and the reason I told that story is that he’s the person that everybody would dismiss. He was banned from everywhere. People would look at him and think he’s the problem. But once you get to know people and see beyond that and inside of that, there’s this really soft core that wants safely and love and meaning.

He would feed the animals at his camp. He volunteered at the Martha O’Brien Center to pack food boxes for people. It’s the most random thing I could ever imagine him doing, but he was a very solid volunteer for them for over a year. He had a really tender spot and gave me a bird feeder once he found in a dumpster.

Everybody has a story, and nobody should be dismissed because of what we see on the outside. And everybody deserves housing and healing.

What can you do to stop homeless deaths?

Join us in working toward a world in which no

life is lived or lost in homelessness.