Primary audience: health centers, free and charitable clinics, safety-net hospitals

Meeting people’s needs wherever they may be

As the increase of people living unsheltered drives the overall rise in homelessness, providers increasingly understand that their services must be accessible wherever their clients reside. We must meet people where they are, including indoor locations like soup kitchens, shelters, and libraries, in addition to outdoor locations like encampments, wooded areas, and sidewalks. But how do you get clinical services out there?

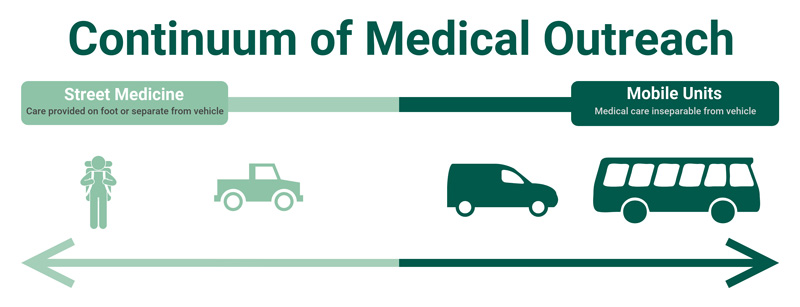

Medical outreach comprises a continuum of service delivery methods. On one end is street medicine, otherwise known as backpack medicine (especially in communities where outdoor homelessness is hardly urban), which is direct care for people living unsheltered in the place where they reside.

On the other end is an RV, the largest of which have multiple exam rooms, wheelchair lifts, and other bells and whistles (for example, check out this six-minute virtual tour of New Horizon Family Health Services’ 35-foot MMU!).

In between are Mobile Medical Units (MMU) of different sizes, some of which constitute the clinic itself whereas others simply transport the outreach team: but here there is a philosophical line.

Services on a Vehicle are not Street Medicine

According to our colleagues at the Street Medicine Institute, services provided on a health center’s mobile clinic do not constitute street medicine because it conflicts with their core ethic of suspending the traditional patient-provider power dynamic.

Those who sleep outside are often most mistrustful of institutions for valid reasons, not least of which is the trauma they have experienced in medical settings. So going to where clients reside is to meet them on their own territory on their own terms, altering the power differential; we are guests in their space just as we would be in someone’s house.

The MMU, on the other hand, is the health center’s domain. This distinction is theoretical but not trivial. Indeed the values we bring to this work inform everything about how we carry it out (explore this further in our recent webinar, Promoting Safety in Street Outreach).

But arguing that MMUs are not street medicine is not to invalidate them. Some patients, in fact, may prefer coming aboard your RV, and such vehicles can be more advantageous for providers. Furthermore, street medicine and MMUs can complement one another, and one may be a precursor to the other.

Long-term street outreach may present opportunities to expand services to a site, especially services such as dental care, which can be difficult to perform as street medicine. Conversely, street medicine may be more successful in areas where MMUs struggle to engage clients. So, let us consider the pros and cons of each approach.

Compliance (for FQHCs)

From a health center compliance perspective, the MMU is more straightforward. The vehicle itself is the service site, making it eligible for FTCA (malpractice insurance) coverage, Medicaid reimbursement, and easily identifiable in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) scope of the project.

HRSA is more accustomed to compliance issues facing MMUs and may, in turn, be less familiar with the range of services comprising street medicine. While health centers have been providing medical outreach (without vehicles) for decades, there remains inconsistency in how health centers account for street medicine in their scope of the project and some HRSA project officers may not recognize the legitimacy of this service as a site unto itself.

For health center readers considering adding street medicine to your scope, the key HRSA document is PIN 2008-01: carefully study the definitions of intermittent sites and note the mention of “portable clinical care” as an “other activity/location” to be registered in Form 5C.

State Medicaid agencies are even less consistently familiar with street medicine. In one state, for example, one HCH program has been successfully billing for street medicine for decades, but another we have been working with is being denied reimbursement by the very same office.

Billing for street medicine is a major hurdle, though may be gaining steam with California’s recent policy shift to recognize “field” as a legitimate place-of-service code.

Expenses

MMUs are notoriously expensive both to acquire and to maintain. Repairs routinely disrupt services for MMUs and, these days, are hampered by supply chain issues affecting the whole motor vehicle industry.

Some health centers send their staff to encampments on their own when the MMU is out of commission, but unless street medicine is also included in their scope of the project, this is a compliance risk.

While expensive, the previously mentioned Medicaid reimbursement opportunities and HRSA recognition partially offset this investment compared to inconsistently fundable street medicine.

Moreover, the MMU is a mobile advertisement for the health center, quite literally like a bus ad, and is a straightforward fundraising project from a development professional’s perspective.

Notwithstanding reimbursement, though, street medicine is certainly cheaper to operate, and both services may reduce overall expenditures by reducing the utilization of emergency services.

Finally, bear in mind that all strategies on the medical outreach continuum face distinct pressure to justify their existence since provider productivity (i.e., number of billable visits) is generally lower than brick-and-mortar care.

Photo: Alameda County HCH

Photo: Alameda County HCH

Agility and Service Availability

A couple of years ago, a group of NHCHC members spontaneously convened to explore the question “what’s the smallest possible mobile medical unit?” The rationale was that giant RVs were not just expensive but also cumbersome.

Their drivers sometimes require commercial driver’s licenses (CDLs) and special training, and it can be difficult to find ample space to park large vehicles. The smaller the unit, the easier it is to access hard-to-reach areas. These members were after the smallest available vehicle where one can still comfortably stand up.

Alameda County Health Care for the Homeless recently realized its vision with eleven agile vehicles (pictured below) covering the Oakland area’s neighborhoods.

Smaller vehicles can also respond to sudden needs that arise in the community.

Street medicine or smaller MMUs can change locations more easily and to provide care at new locations without some of the logistical challenges presented by a large RV, which often limit the number of sites an RV can visit in the course of a day.

Photo: Alameda County HCH

Photo: Alameda County HCH

But the smaller the vehicle, the fewer services are available. This is especially true for dental services and others that require more equipment. While experienced street medicine providers claim they can provide nearly every service they would routinely provide in a brick-and-mortar health center, a vehicle with storage and electricity certainly makes medical care easier.

Safety

Maintaining safety for both staff and clients is vital no matter the venue in which care is provided (and this overall issue is a priority at the NHCHC), but outdoor locations bring their own challenges in part because providers are entering the clients’ domain. While this is intentional and important, as discussed earlier, it brings similar risk as entering someone’s house.

Distinct strategies and skills are necessary for anyone providing services in outdoor locations. Indeed, these particular risks may persuade some to prioritize MMUs over street medicine. But these perceived threats to safety should not sacrifice the accessibility of care.

Providing care in a vehicle behind a closed door, moreover, may be riskier than an encampment in public view. In addition, large medical vehicles are more likely to be vandalized due to supplies MMUs may be carrying.

Again we recommend our recent webinar that confronts this issue within the confines of one hour, in addition to other NHCHC resources on workplace safety.

In Conclusion

It may be the case that health centers focus on MMUs because they are unaware of the opportunities street medicine contains.

Shadowing an experienced street medicine provider may reveal the breadth of options and accentuate its advantages – or, indeed, its drawbacks.

Regardless, health centers should carefully weigh the pros and cons associated with any strategy on the continuum of medical outreach and may conclude that multiple delivery methods are necessary. As with any new service, starting small may be the wisest.

Special thanks to Katie League for her contributions to this post.

Resources

- Street Medicine Institute

- Mobile Healthcare Association

- Virtual Tour of Mobile Medical Unit in South Carolina

- Recordings of 2021 Learning Collaborative on Mobile Medical Units

- Outreach resource page

- Workplace safety resource page